“Are you crafty?” the librarian asked as she got ready to teach me how to repair books. “Only I find people that are good at sewing or needlework usually are better at repairing books.”

“No,” I said, because honestly sewing machines make me breakout in hives and every time my mother tried to teach me to knit she gave up, claiming I did it backwards.

I could tell by the librarian’s face she was having second thoughts. Like maybe I’d be so bad at gluing the book’s broken spine back together, she’d regret letting me near it. She was probably right to worry, because I have been known to glue bits of construction paper to my bangs while trying to make a craft for story time. Still wanting to reassure her, I offered the thing I was good at.

“I can stitch people up really well, though,” I told her.

She blinked, slowly. Like I could have actually timed how long her eyes were closed. One one-thousand, two one-thousand. Then they opened and she picked up the bottle of glue and began to explain.

It didn’t dawn on me, until recently, that if I rattled off the few things I am good at – beyond taking tests and remembering obscure facts and maybe reading – things that might actually be useful to the world – the world pretty much all involve poking needles into flesh. Like taking blood samples from sheep, or suturing people. Useful at least in the apocalypse.

I’d been giving shots to sheep and humans for a while before I learned to suture. If I’m honest, I didn’t actually like it. I always felt a little guilty vaccinating sheep or drawing their blood, because I couldn’t explain to them why I was doing it. When I became a nurse and started poking people, you would have thought it would get easier. People after all could understand that it wasn’t personal. I was actually trying to help them. Infants though, proved a moving target. And parents were pretty useless. Often crying as much as their babies did.

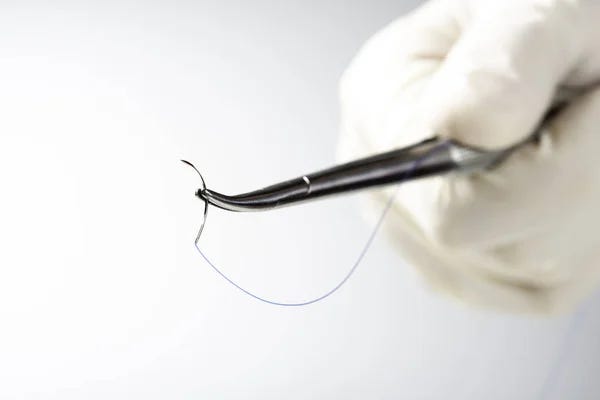

Once I got to be a nurse practitioner though, I got signed up for a course on learning to suture. So, I sat at the table with my pig’s leg for practicing on and listened attentively to the nurse practitioner instructing us on how to suture. She demonstrated how to hold the needle, create the loop, make the stitch. Once she was done talking, we all got to work stitching up the cuts in our severed pig’s leg. The pig, obviously, couldn’t squeal or dodge the needle and so the process seemed almost meditative.

I stuck the curved needle into on side of the gash, pulled the thread through with the hemostat, pierced the flesh on the other side, pulled needle and thread through again. Holding the needle in one hand, I laid the hemostat around the thread on the far side of the gash, made two loops, clasped the thread on the near side of the gash with the hemostat, and pulled it through, which closed the gap and created a nice knot. A snip of the scissors and I started the next stitch. Poke, poke, loop, loop, grasp, pull, snip. Poke, poke, loop, loop, grasp, pull, snip. A row of orderly, uniform stitches appeared.

After a moment, I felt someone standing watching and turned to see the instructor observing my every move.

“You’ve done this before,” she said.

I shook my head, although if I was honest, I had. But that had been twenty years before and I’d only done it a couple times on rats. Somehow, explaining that as an animal science undergrad I had castrated and spayed rats in a repro lab and then learned to suture them up just seemed too hard to explain.

“You’re very good,” she said.

It turned out the instructor worked in a local OR and her job was pretty much to close up patients after surgery. It sounded like a dream job. Poking unconscious people, patients who couldn’t talk or jump or fight back. If I had been able to get that job, I might be a nurse practitioner still.

Back at the clinic where I worked, my first real patient needing sutures arrived just a few weeks later.

“Come on,” said the senior nurse practitioner, “let’s see what you learnt.”

I walked into to find a man in his forties with a nice neat gash on his arm. I tried not to shake as he, and the other NP watched me get out the lidocaine, a syringe, sterile equipment. I set up the sterile field, lined up my tools, and prayed my hands didn’t shake.

“I’ll just put in some lidocaine to numb it,” I told the guy. “This will sting.”

For my pig leg, I hadn’t had to numb it, but this guy was alive and attached to his arm. He winced as I poked him with the syringe of lidocaine up and down the gash. I waited a few minutes for the numbness to take hold and then began my first stitch. The patient and the other NP watched me intently, but I let myself fall into the rhythm. Poke, poke, loop, loop, grasp, pull, snip.

People talk about getting into the flow or zone. It works for athletes and musicians, but for me taking tests and suturing people are pretty much the only times I’ve ever been in the zone.

In less than ten minutes, I had a nice row of even stitches. The nurse went to dress the man’s arm.

“Thanks,” he said.

“Come back in ten days to get them out,” I said.

As we walked into the hall, the head NP said, “you’re better than I am. You get to do all the suturing now.”

Now, having left health care years ago, I don’t get to poke, poke, loop, loop, grasp, pull, snip at all. But whenever my fantasy writing friends and I talk about who’s got the skills for the zombie apocalypse, I always say “I can stitch people up.” I may not have wicked sword skills to take off a zombie’s head – but I might be able to stitch up a human here or there. And that’s nothing to sneeze at.

Good to know you have a resume for the apocolyse.

Cool things I did know about you or how to do myself.